XintraLabs - Waifu University Ransomware Case Writeup

Scenario:

Waifu University's cyber team has called you after their IT teams reported a number of servers with files that aren't opening and have a strange extension. On your scoping call, the victim also said they had identified a ransom note stating their data has been stolen. When asked about any earlier signs, the victim mentioned some strange, failed login activity early in March 2024 in their Entra ID, but it wasn't of concern at the time.

Ransomware typically avoids system files to not cause crashes in the system, which also happens to be where a lot of forensic evidence is! You have been provided triage images of the hosts and log exports from the relevant systems.

The Waifu University team took triage collections from the affected hosts using the account WAIFU\kscanlan6 at approximately 2024-03-07 05:00:00 UTC. Consider activity after this point related to the response.

I've tried to make a point here to avoid directly giving the answers, they may be assumed or present in the screenshots provided in hope this proves as a reference as opposed to a fill the blank exercise.

Network Map:

Analysis & Questions:

Initial Notes:

I'm doing as much as possible on the host itself and outside of ELK. I'm making a point to use a variety of sources as sometimes leaning on a specific data source and it not being available in a case can really cripple your response.

- Failed login activity early in March 2024 in their Entra ID

- Account WAIFU\kscanlan6 at approximately 2024-03-07 05:00:00 UTC

1: Scoping the incident

Question 1:

What was the domain the threat actor has requested the victim to visit in order to further communications?

I made a point to extract the Triage images alongside the Evidence zip archives and then navigated to the CC-JMP-01 Triage image to review the filesystem. Ransomware commonly puts the 'readme' file in an obvious location, such as the desktop. Simply double-click the image to browse different user's Desktops (noting that kscanlan6 was used for acquisition).

Here we find the information required, such as the onion domain and the filename.

Question 2:

What was the file name of the ransom note left behind by the ransomware?

^ :)

Question 3:

What was the file extension the ransomware added to encrypted files?

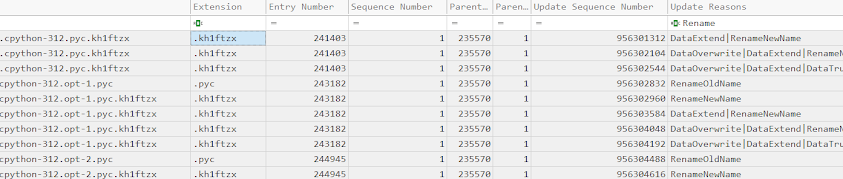

For this we'll be using the USNjournal as it will quickly provide the information we require. Filtering for 'Rename' in the Update Reasons we find an anomaly quickly.

2: Initial Access via Entra ID

Question 1:

Our security team mentioned that there was a number of failed logons to the victim’s Identity Provider (Entra ID).

What was the full user agent string that was responsible for these attempts?

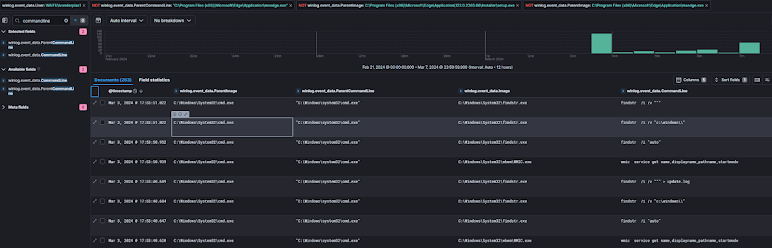

So we know these were observed early March, heading to ELK and reviewing the Azure Logs, where our primary dataset of interest will be 'azure.activitylogs.category'. Now we simply need to filter for failed logons. Here - ManageEngine (50126) is our azure.activitylogs.result_type id of interest. Here our event count is drastically reduced to 32.azure.activitylogs.category:SignInLogs AND azure.activitylogs.result_type: 50126

By expanding the event (stretch icon on the left-hand side of the event block), we can quickly see the user-agent.

Question 2:

What was the cloud provider the threat actor used to proxy their requests? Please use the acronym.

Example: GCP

Using one of the IPs, use your tool of choice to retrieve the relevant information on said IP.

Question 3:

How many unique users did the threat actor attempt to authenticate with?

With the events of interest, adding azure.activitylogs.identity_name, we can head to field statistics and quickly review the targeted users.

Question 4:

What was the User Principal Name (UPN) of the user the threat actor succeeded in accessing?

We require a static 'searchable' data point. We have IPs, but there's 32 of them. We have some interesting ones such as the field source.as.organization.name being 'AMAZON-02'.azure.activitylogs.identity_name:* AND source.as.organization.name:"AMAZON-02"

We see one result anomaly here:

"Due to a configuration change made by your administrator, or because you moved to a new location, you must use multi-factor authentication to access the resource."

Indicating a successful auth, but it was snagged. By filtering on this result and expanding the event, we get the UPN.

Question 5:

What was the most likely method the threat actor was able to authenticate to the VPN that was protected by MFA?

[ ] MFA push fatigue

[ ] Session Hijacking

[ ] SIM Hacking

[ ] App Consent

Turning our attention to the user, we now have a single point of review. Filtering on the user alone, we get some insight into what activity occurred against their account, helping us determine the MFA 'bypass'. (Note: the org name will no longer be needed here.) (Filter on the time period of interest to remove FP events.)

Reviewing the output, we see a large volume of 'Authentication failed during strong authentication request.' over a short period of time, indicating a large volume of MFA pushes were invoked.

Following this, we see some successful logons.

We can also get some insight into the user's initial denies.

Question 6:

What was the IP that successfully logged into the environment?

With the above information, we can follow the activity timeline and determine the IP (with the result description of '-').

Reviewing the 0x30 timestamps, we see anomalies compared to other files. While they may seem understandable, the timestamps indicate this is a clue.

Reviewing '20240329012439_Windows10Creators_SYSTEM_AppCompatCache', we observe further anomalies.

We confirm our suspicions by reviewing process executions (Sysmon Event ID 1 contains hashes).

Question 4: Malicious Process Dump Analysis

What was the IP the beacon talks to?

The Sysmon event logs didn’t record any network activity due to the configuration's limitations.

Using the process dump provided in malicious_process.zip (password: the process name of the binary).

Assuming this is a fresh sample and no hash hits return during OSINT we need another approach. It is quite obvious in this case with CSCE being present on our tools, but we could opt for Yara or another static analysis tool to give us further insight. https://thedfirreport.com/2021/08/29/cobalt-strike-a-defenders-guide/ Now we have an indication that this is Cobalt Strike, we can use CSCE to extract relevant information.

Question 5:

Based on the same process dump, can you identify the domain the beacon uses in the host header?

^

Additionally, we get the sacrificial process for both x32 and x64 systems.

6: Accessing Volume Shadow Copies

Question 1:

What was the timestamp of the command that the threat actor used to access a volume shadow copy of the beachhead host?

We got this information earlier when looking at 'service' string inside Sysmon logs. Filtering specifically for 'shadow,' we see the following.

Question 2:

What was the file name that was responsible for running the volume shadow copy command?

^

7: Looking Around The Network

Question 1:

The threat actor was able to open a file that was supposed to be in a hidden share from the beachhead host. What was the name of the file?

Note: Just have one extension, not two, in the answer

Let's use one Registry Artifacts to answer this one—enter RecentDocs found in C:\Labs\Evidence\WaifuUniversity\ProcessedEvidence\CC-JMP-01\Registry\20240329015008\20240329015008_RecentDocs_C_Users_ivanderplas1_NTUSER.DAT.csv.

This gives us a quick overview of documents (split by ext) that were opened by the user.

Question 2:

What discovery tool did the threat actor create through their beacon?

We know the Cobalt Beacon was 'python.exe,' so reviewing Sysmon file create events (ID 11), we see the following.

Question 3:

Was the threat actor successful in executing this tool?

No evidence suggests it executed, but to cover spotty logs and file renames, let’s check some other artifacts. We will use USNJournal for checking for a rename. A quick way instead of waffling through the actions is to simply get the Entry Number of 414719 and then remove our 'Sharphound' string search. No indication of renaming.

Based on the incident recently happening, we can check the shortcuts and/or prefetch of the system to verify if it was run. No evidence of said binary running was found.

Question 4:

What group did the malicious process enumerate on the beachhead host?

A quick win here, initially searching for Event ID 4799, and quickly reviewing the calling process, we find our beacon.

And inside the Event, we find the group that was enumerated.

8: Domain Dominance

Question 1:

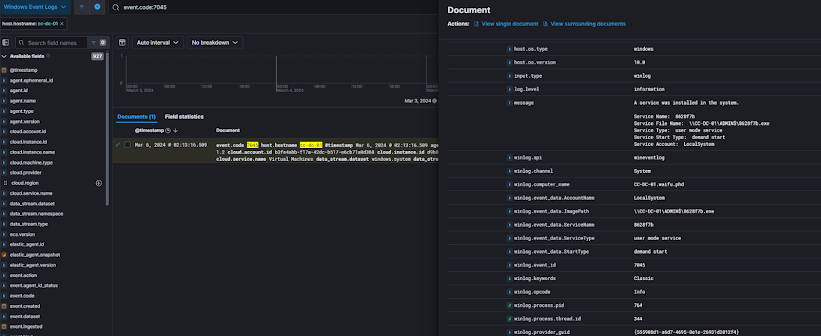

What was the name of the malicious service that the threat actor attempted to install on the Domain Controller?

Reviewing 7045 on the DC, we find one entry.

Question 2:

What was the possible operating system distribution the threat actor is using?

As seen earlier, logon events can leak 'Workstation Name.' Querying this and summarizing the workstations, we see the following.

Question 3:

What was the name of the DLL installed onto one of the domain controller's processes to monitor for credentials?

Time to extract the DC Processed Evidence unless you want to use ELK and open up the EventLogs. Checking Event ID 11 of Sysmon, I reviewed some processes of interest, and upon checking PowerShell, we see a suspicious DLL part of AADInternals.

PTA stands for Pass Through Authentication; "Microsoft Entra pass-through authentication allows your users to sign in to both on-premises and cloud-based applications using the same passwords. This feature provides your users a better experience - one less password to remember, and reduces IT helpdesk costs because your users are less likely to forget how to sign in."

Question 4:

What was the file name of the process that this DLL was injected into?

Checking Process Execution referencing the DLL name (minus the extension), we see two critical entries. The first proves the prior question and the target PID for injection.

Second, a PTASpy.csv, indicating an output for the tool.

And as expected, it injected into the AD Agent for sniffing and dumping passwords.

Question 5:

What is the likely user that had their credentials recorded by the DLL?As the file was encrypted, we will need to use alternate means to determine this. We can correlate the CSV write or modified timestamp to the nearest authentication.

9: Accessing the Good Stuff

Question 1:

Which account did the threat actor access the SQL server with via RDP?

Reviewing Event 4624 and Logon Type 10 on or after 2024-03-06, we see the following. Based on the DLL injection timestamp and so on, we can conclude that CC-Admin was used.

Question 2:

The University admins noticed a strange file in the documents folder of the admin user for the SQL server, which was created during the intrusion. What was the earliest MFT Entry ID for the file name in this path?

We see a few files with the encrypted extension.

As the entry will be updated in the MFT, we need to use the USNJournal. Simply providing the filename will give us the associated MFT Entry Number. (LNKs are just shortcuts to said file, not the file itself.)

10: Release the Ransomware

Question 1:

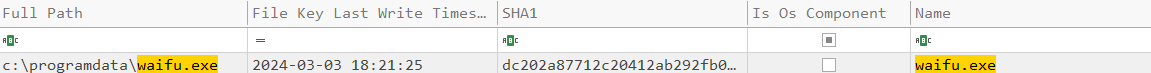

What was the name of the ransomware binary?

Based on our previous efforts, we can easily get this using Sysmon's Event ID 11 paired with the extension.

Question 4:

What was the access token provided to the binary to decrypt the payload?

Now that we know the binary name is print64.exe, we can review command line events for said binary.

We see a lot of typical Ransomware tradecraft in this one panel.

Comments

Post a Comment